Climbing Grades: Systems, Charts, and Conversion (2024 Guide)

How do rock climbers, mountaineers, ice climbers, and other adventurers decide where and what to climb? Do they explore crags and mountains for tantalizingly steep cliff faces, seeking dramatic lines through beautifully aesthetic rock and snow, then gear up and go for the send in a bold push to the summit?

Yes, this idyllic scenario describes an occasional first ascent. But generally speaking, climbers have some prior knowledge of a particular region, climbing area, and the individual routes wherever they intend to climb. In the climber’s dictionary, slang for inside info about an area or a route is “beta.” As in, “What’s the beta on that sick boulder problem?”

Climbers generally desire several vital pieces of information when researching a place to climb: an accurate route description including location and the consensus grade (or rating) of a route or bouldering problem. Route beta can come from an internet source (like Mountain Project, 99boulders.com, etc.), a printed guidebook, or locally compiled and shared data within a climbing community.

What Are Climbing Grades?

Climbing grades describe the objective difficulty of a climb and are organized into grading systems based on the climbing style and the region.

Indeed, as there are many climbing styles, many grading systems have emerged throughout climbing history to cover the different types of movement and technologies climbers use to ascend varied terrains like rock, ice, and snow.

The most commonly used grading systems were developed for technical rock climbing styles of sport climbing, trad climbing, and bouldering. These climbing methods can also be categorized as “free” climbing, which means a climber ascends using only natural features to assist their upward progress. A free climber only uses a rope and gear to prevent dangerous falls and injury, but they never place their body weight on the rope while climbing a pitch.

“Aid” climbing is when climbers use drilled bolts and other gear to assist their progress on rock climbing routes. It has its own particular grading system.

Other climbing styles with their own grade systems are ice climbing, mixed (rock/ice) climbing, and mountaineering.

The most popular systems for grading climbs worldwide are:

| Roped Climbing | Bouldering |

|---|---|

| Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) | V-Scale |

| French System | Fontainebleau (often shortened as “Font”) |

Several other countries and regions use their unique grading systems for technical climbing, including Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

What’s the Purpose of Climbing Grades?

Why do climbers create and use grading systems? When climbers attempt to ascend a new route, there are many benefits to learning information from previous climbing parties who successfully climbed the route before them.

One of the most vital pieces of information relevant to a known route is the grade or difficulty rating. Climbing grades for rock and alpine routes are always expressed on a scale using letters and numbers.

Traditionally, the first party to ascend a route suggests its original grade. Sometimes, the grade can also come from parties attempting and failing to climb the route cleanly. Grading climbs accurately is a skill of its own and requires extensive experience climbing many routes in several different environments.

These are some of the most important reasons for climbers to understand grades and research difficulty ratings for their climbing objectives.

Safety

For climbers who want to control their safety and manage risk, knowing the difficulty grade of a climbing route before attempting it is critical.

While modern sport climbing equipment and techniques have made climbing much safer than it may have been in the past, there is always a risk of injury when a lead climber falls. And many climbers would agree that trad and aid climbing falls present even greater injury risks.

For climbers who prefer to minimize risk by minimizing the chance of dangerous falls, foreknowledge of a climbing route’s difficulty is a priority.

Choosing a Climbing Route or Area

Many climbers have their most productive, challenging, and memorable days of climbing when they can climb routes at or near their limit. The best way to climb the most routes at this optimal level of difficulty is to climb at an area where you can find multiple routes of appropriate difficulty reasonably close together.

Knowing what grade of difficulty you prefer helps you research and choose the best area to climb at, where you can efficiently do the most climbs without excessive hiking. You can also avoid areas with too hard or easy routes for your taste.

Often climbing parties include individuals with widely differing levels of ability. When planning a trip with a diverse group of climbers, being aware of both your party’s abilities and the range of route grades at your potential destinations is key to a successful excursion.

Progression of Abilities

Climbers use climbing grades to test and compare their progress in the development of their climbing abilities. You might set climbing goals in terms of your ability to climb a particular grade or route, which can be motivation to train harder and get stronger.

It is common wisdom in the climbing community for beginners to advance up the grades fairly methodically when lead climbing. A lead climber who can barely lead 5.10a without a fall but who wants to push their limits to 5.11a generally will try and succeed first at leading 5.10b, 5.10c, and 5.10d routes before moving on to attempt a 5.11a.

To follow this advice, one obviously needs to know the grades of the routes they are climbing.

Downsides to Climbing Grades

Of course, there are always less desirable features of any standardized system, and climbers may criticize the use of grades for different reasons.

First, the relative nature of route grades means they are highly subjective and inconsistent, depending on who assigns them and that person’s or party’s experience. Regional customs and conventions also lead to differing perceptions of the proper grade. Grades in California may be stiffer than those in Colorado. In Céüse (France), the grades may feel more strenuous than Rifle (Colorado).

So, the argument goes, if they are so inaccurate, why use them at all?

Knowing a route’s grade beforehand can lead to negative mental feedback for some climbers. If you believe in your mind that a route is too difficult based on its published rating, that knowledge can cause stress that interferes with your thinking and movement on the rock. Sometimes not knowing that something is “too hard” allows a climber to get in the flow and climb harder than they thought possible.

For most of the climbing world, though, the benefits of climbing grading systems greatly outweigh the few disadvantages.

Technical Rock Climbing Grades

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS)

The Yosemite decimal system (YDS) is a system that evolved over many decades and was initially codified by the Sierra Club in California. The YDS is a flexible grading system that can describe the length, difficulty, and difficulty of protection on a given route, from a single-pitch sport climb to a 30-pitch trad climb.

The Yosemite decimal system also describes non-technical hikes, and mountain summit climbs. The system starts at Class 1, a rating that indicates a hike on a relatively flat trail without extremely steep terrain.

At Class 2, a hiker may need to occasionally put their hands down for balance or assist with upward progress. Some people call this scrambling. Generally, hikers will not encounter significant or hazardous exposure to complete the route at this level.

Class 3 involves more use of the hands and upper body for balance and maintain progress and can pose dangerous fall potential in the case of a slip or misstep. Some hikers/climbers may choose to wear helmets and use ropes for protection at this level. There is more likelihood of longer stretches of sustained climbing.

As climbing difficulty progresses into Class 4, most people use ropes and protection due to steepness and exposure. Unroped climbers risk severe injury or fatality in the event of a fall.

Technical rock climbing begins with routes reaching the Class 5 level. The YDS only applies to rock climbing routes, not ice or mixed rock/ice climbing routes. Class 5 is when routes of sustained hard climbing begin, and climbers must continuously use both hands and feet for security.

At the YDS scale’s origin, the range was intended to be 5.0 to 5.9. However, climbers realized that much harder climbs were possible with the advent of modern climbing shoes, better training, and more skilled techniques. So, the YDS scale became open-ended and allowed the top end of the scale to continue expanding.

Technical Rock Climbing Grades

At Class 5, the YDS grades become more precisely defined by adding additional numerals and letters. The current range is 5.0 to 5.15d, meaning the hardest rock climbing route at this time is rated 5.15d.

That’s how much modern climbers’ skill, strength, and technology have improved over the past 75 years. As a result, the “most difficult” climb thought possible has advanced from 5.9 to the hardest today at 5.15d (check out the video of Adam Ondra climbing Silence in 2017).

How Are Route Grades Determined?

Route difficulty ratings usually reflect several aspects of a climb: the physical difficulty of surmounting the most demanding move, the overall length and endurance required, and how sustained the difficulty of climbing is from top to bottom of the entire pitch.

These criteria are subjective, of course, but the idea is that after many different climbers of different body types and abilities offer their individual opinions, they will reach a valid consensus on the route difficulty.

This process can lead to great conflict within the climbing world for some–and entertainment for others. Depending on one’s perspective, route inflation, downgrading, and sandbagging are either sin or art.

While both sport climbing and trad climbing share the same YDS grading system, the techniques involved in crack climbing with gear versus face climbing on expansion bolts make comparing route grades somewhat tricky. In other words, a climber who easily climbs routes at a sport grade of 5.9 may find a trad route at the same grade an entirely alien experience.

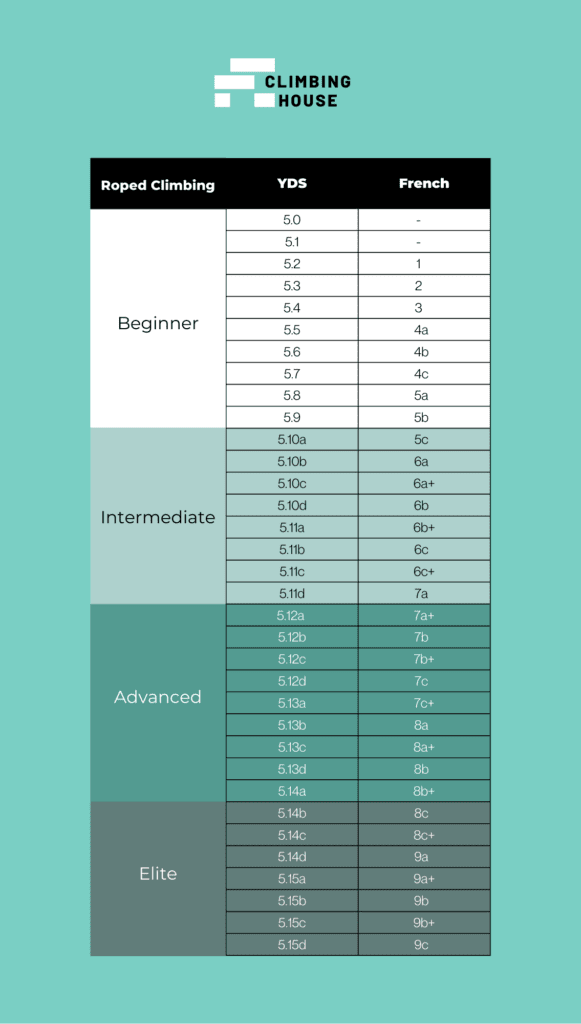

YDS Grade Difficulty Chart

As noted, the current YDS difficulty scale for technical grades ranges from 5.0 to 5.15d. Here’s a table showing the exact progression of the Yosemite decimal system:

| YDS | French |

|---|---|

| 5.0 | – |

| 5.1 | – |

| 5.2 | 1 |

| 5.3 | 2 |

| 5.4 | 3 |

| 5.5 | 4a |

| 5.6 | 4b |

| 5.7 | 4c |

| 5.8 | 5a |

| 5.9 | 5b |

| 5.10a | 5c |

| 5.10b | 6a |

| 5.10c | 6a+ |

| 5.10d | 6b |

| 5.11a | 6b+ |

| 5.11b | 6c |

| 5.11c | 6c+ |

| 5.11d | 7a |

| 5.12a | 7a+ |

| 5.12b | 7b |

| 5.12c | 7b+ |

| 5.12d | 7c |

| 5.13a | 7c+ |

| 5.13b | 8a |

| 5.13c | 8a+ |

| 5.13d | 8b |

| 5.14a | 8b+ |

| 5.14b | 8c |

| 5.14c | 8c+ |

| 5.14d | 9a |

| 5.15a | 9a+ |

| 5.15b | 9b |

| 5.15c | 9b+ |

| 5.15d | 9c |

Rating Objective Dangers

The YDS system includes a rating to inform climbers of potential fall danger, which may or may not be published depending on one’s source of information. This scale is similar to America’s movie rating system, so it will be familiar to many.

When applied to sport climbing routes, this scale generally refers to the potential for ground fall, length of a possible fall, or the possibility of hitting a ledge or other object during a lead fall. For trad routes, all of these apply, along with the difficulty of gear placements that may lead to longer or more hazardous falls.

Here’s the scale:

- G Crux moves are well protected by gear or bolts, placements are all solid, and there are no ledges or other objects the leader or follower is likely to strike in the event of a fall.

- PG Gear is still solid in all placements, but may be somewhat more run out. Slightly greater risk of injury in the event of a leader fall due to longer falls and/or obstacles in the fall line.

- PG13 Greater risk of serious injury in the event of a fall due to environmental factors, and/or longer runouts between solid gear placements.

- R A fall poses risk of serious injury due to the long gaps between gear or other available protection. A leader is likely to hit the ground or a ledge upon falling.

- X A lead fall is almost certain to result in severe injury or death. Extremely run out and difficult or impossible to protect with reliable gear.

The French Grading System

European climbers developed the French rating system independently, but the scale works very similarly to the YDS. This scale is used in much of Europe and worldwide, making it the second most commonly used system for roped climbing on rock.

Refer to the table shown in the Yosemite decimal system description above to view the current progression of the French system. At present, this system ranges from 1 to 9c, but like the V scale and YDS, it is open-ended and will most certainly expand in the future.

Other Significant Rock Climbing Grading Systems

British Climbing Grades

The United Kingdom uses French ratings for sport routes, but it has its own system for UK trad grades that incorporates two grading systems. This includes one rating for technical difficulty and one rating for overall difficulty.

The technical grading scale is easy to understand, as it relies on the climb’s hardest, most physically demanding move. The technical difficulty is the same, whether that be one single move or a number of equally hard moves.

Like the YDS, the British scale officially starts at 1, but technical climbing starts at the 4a grade (about 5.5 YDS, 3/4a French). The scale may appear similar to the French rating scale, but the top grade in the British scale is currently 7c, with British grades normally perceived as harder than French grades of the same number.

The second part of the British trad grade is an adjectival rating intended to describe an overall difficulty. This is an alphanumeric rating that begins at “M” for Moderate. The remaining scale continues thusly:

- M (Moderate)

- D (Difficult)

- VD (Very Difficult)

- HVD (Hard Very Difficult)

- S (Severe)

- HS (Hard Severe)

- VS (Very Severe)

- HVS (Hard Very Severe)

- E1 – E11 (Extreme)

The E category is open-ended and currently runs from E1 to E11. This adjectival rating takes into account a number of aspects, from the quantity and quality of placements to the steepness of the cliff and the number of rest spots. In practical terms, it also describes an ascending level of risk due to any number of factors.

Australian Climbing Grades

The Australian climbing grade scale for technical scrambling and rock routes, another open-ended rating system, runs from 1 (~YDS 3) to 39 (5.15d).

South African rock climbing grades are very similar to Australian, with the exception that the upper end of the scale is currently at 41.

Bouldering Grades

V-Scale Grades

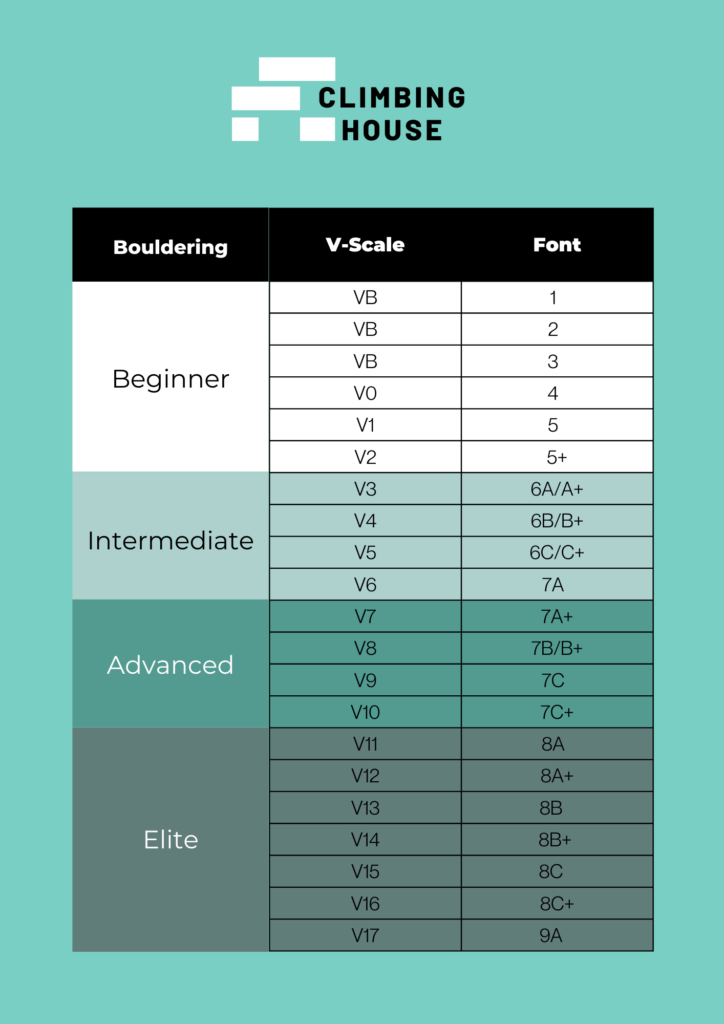

The most popular rating system for bouldering problems in North America is the V-Scale, first conceived by John Sherman in the 1980s and now used throughout the United States and in many other locales.

Bouldering grades define not only the most difficult move or sequence on the problem but also whether there are multiple difficult moves that require more endurance. That is, adding 6 moves of V9 difficulty to an existing V9 problem could easily push the overall difficulty to V10, even if no individual move is deemed harder than V9.

Because boulder problems are by design shorter than the typical rock route, they tend to be more strenuous and powerful. That is why the V-Scale starts at a fairly high level of effort compared to the YDS.

In other words, the lowest grade on the V-Scale, V0, requires a climber to complete moves that would be graded 5.10d on the Yosemite decimal system.

One other feature of the V scale, like the YDS grade system, is its open-ended nature. The most difficult problems in the world, according to the opinions of the world’s top boulderers, are currently graded at V16 or perhaps V17. Within the next few years, we are likely to see a new problem that pushes the current standard up to V18.

When bouldering problems are considered easier than the V0 rating in the V scale, they may be shown with a “VB” rating.

The chart below shows the progression of the current V scale, with an approximately equivalent YDS rating for comparison:

| V-Scale | YDS |

|---|---|

| V0 | 5.10a/b |

| V1 | 5.10c/d |

| V2 | 5.11a/b |

| V3 | 5.11c/d |

| V4 | 5.12a |

| V5 | 5.12b/c |

| V6 | 5.12d |

| V7 | 5.13a/b |

| V8 | 5.13c |

| V9 | 5.13d |

| V10 | 5.14a |

| V11 | 5.14b |

| V12 | 5.14c |

| V13 | 5.14d |

| V14 | 5.15a |

| V15 | 5.15b |

| V16 | 5.15c |

| V17 | 5.15d |

| V18 |

The Font System

The second most widely used bouldering grade system is called the Font scale. This system was invented in and is named after, the famed Fontainebleau bouldering area of France.

The Font bouldering grades scale starts at 1 and currently goes to 9A. Here is the Font scale alongside the V scale for comparison:

| V-Scale | Font |

|---|---|

| VB | 1 |

| VB | 2 |

| VB | 3 |

| V0 | 4 |

| V1 | 5 |

| V2 | 5+ |

| V3 | 6A/A+ |

| V4 | 6B/B+ |

| V5 | 6C/C+ |

| V6 | 7A |

| V7 | 7A+ |

| V8 | 7B/B+ |

| V9 | 7C |

| V10 | 7C+ |

| V11 | 8A |

| V12 | 8A+ |

| V13 | 8B |

| V14 | 8B+ |

| V15 | 8C |

| V16 | 8C+ |

| V17 | 9A |

Grades Vary by Climbing Area and Age

A climbing route’s original grade is traditionally agreed upon by the party who first ascends the route, and offered as a courtesy to later parties attempting the climb. Most route pioneers are happy to have a second or third opinion on the climb’s rating, in the interest of establishing a consensus that a majority of climbers will find reasonable.

Given this extremely subjective and informal system that has been adopted in the climbing community, the perceived difficulty of a 5.9 sport climb, for example, can span a wide range.

Older rock climbing routes were graded at a time when the upper limit of the grading range was 5.9 or 5.10. Many a strong climber has confidently tied in at the bottom of an alleged 5.8 warm-up originally put up in the 1960s or 70s, only to be spit off the wall at some diabolical crux while wondering what just happened to their skills and ego.

Gym Climbing Grades vs. Outdoor Climbing Grades

In North America, most climbers find that indoor routes are graded more generously than outdoors. That is, a 5.10a sport climb in the gym feels easier to most people than most outdoor 5.10a routes.

Part of the discrepancy is certainly due to the greater difficulty in identifying and grasping holds on real rock, compared to a route where all the holds are clearly marked and visible.

Other large variables are the experience of a gym’s route setters and local convention. A city or region with a large and experienced climbing population may tend to favor stiffer grades, relative to indoor climbing facilities patronized by less experienced climbers.

New outdoor climbers should set their expectations accordingly. Just because you feel solid and safe leading 5.10c indoors, don’t expect an outdoor 5.10c to give you the same confidence.

Many rock climbing gyms have developed their own unique grading systems for use only in that facility. For example, rather than adopting the V-scale for bouldering problems, a gym might use the designations E, M, D, and VD (to stand for Easy, Moderate, Difficult, and Very Difficult). These customized ratings help to prevent unrealistic expectations or comparisons between indoor and outdoor climbing grades.

Grading Systems for Other Styles of Climbing

Big-wall and Aid Climbing

Aid Climbing Ratings

Big wall climbing is practiced on steep, multi-pitch routes that ascend hundreds to thousands of feet of rock. The Holy Land of big walls is Yosemite Valley in California, where many big wall and aid climbing techniques were invented and refined.

As noted earlier, aid climbing involves reaching the top of a route using gear along the way to assist the climber in his or her upward progression. This method is used to climb routes that are considered too difficult or perhaps impossible to free climb.

There are two styles of aid climbing with the same numeric scale, but a different alphabetic prefix. Ratings with an “A” prefix require a hammer and associated protection such as pitons, copperheads, and rivets. Ratings with a “C” prefix are climbed without a hammer; this is “clean” aid.

Toward the upper end of the aid climbing grade range, this style can be a terrifying sport. Hard aid climbers use precisely designed gear that allows them to hang precariously on the tiniest of pockets and ledges. For example, clipping into sheet metal hooks perched on millimeters-wide edges, and taking huge falls into space when those hooks inevitably skitter off.

The grading system for aid climbing essentially describes dangerous fall potential. The higher on the grading scale, the more likely a leader risks long and/or hazardous falls due to difficult and widely spaced gear placements. Hard aid climbs require confidence with extreme technical difficulty, along with a complete disregard for 50-foot shippers!

Aid Climbing Scale

The most widely used scale for grading aid climbing routes is described as follows:

- A0 / C0: Occasional aid moves, often without aiders, on fixed gear or very solid placements. Also known as “French free.”

- A1 / C1: All placements are solid and easy, long enough stretches of aid that aiders are normally used.

- A2 / C2: Good placements with moderate runouts, gear may be tricky but will hold a fall. Minimal risk of fall injury.

- A3 / C3: Many difficult, insecure placements, with accordingly longer fall potential and greater injury risk.

- A4 / C4: Many placements in a row that hold static body weight but will not hold a fall. Long falls up to 100 feet (30 m) are to be expected, increasing the risk of severe injury.

- A5 / C5: Extreme aid climbing. Long stretches or entire pitches without any solid placements that will hold a fall. Scary and mentally intense for even the hardest souls.

A route may have both an aid and a free climbing rating. In fact, some of the most difficult big wall climbs were previously considered unclimbable. When an aid route is unlocked by someone free climbing the entire route, it is conventionally bestowed an updated name and a new YDS rating that is maintained separately from the original aided version.

Big wall climbing routes may combine aid and YDS ratings, along with an NCCS (National Climbing Classification System) grade to describe commitment level (see below). For example, 5.8 A2 Grade VI describes a 2+-day big wall climb with moderately difficult traditional climbing, along with sections of aid climbing with lengthy runouts but decent protection.

Big Wall Ratings

The majority of big wall routes (think 10+ pitches) in places like Yosemite and Zion National Parks are climbed using a combination of free and aid climbing techniques. However, some elite climbers have been able to climb big wall routes cleanly, without any aid.

When big walls are climbed completely free, they are given a two-part grade. The first part is the YDS grade, indicating physical difficulty. The second part is, again, the NCCS rating that roughly describes the time needed to complete the route.

So, a relatively easy technical rock route, the Exum Ridge of Grand Teton in Wyoming, currently has a consensus grade of 5.5 (YDS), Grade III. That means the technical difficulty of this 1700-foot (515 m) route is low, but it requires an average climber most of a day to ascend.

National Climbing Classification System (NCCS) Commitment Grades

On long multi-pitch routes of all sorts, you may see an optional Roman numeral designation that is meant to describe the commitment level of the climb. Commitment is mostly related to the overall length of time it may take an average climber to climb the route, along with the difficulty of retreat and similar factors.

The NCCS standard originated in the US during the 1960s. More climbers were taking on bigger and more ambitious rock routes, so a way to describe the length of an average party’s ascent became very useful.

Be aware of the term “average party,” however. Commitment grades assume that climbers have a thorough knowledge of the techniques and physical prowess needed to succeed on a particular route.

Following is a description of the UIAA’s Commitment scale and the meanings of the grades:

- Grade I: Less than half a day for the technical portion.

- Grade II: Half a day for the technical portion.

- Grade III: Most of a day for the technical portion.

- Grade IV: A full day of technical climbing, generally at least 5.7.

- Grade V: Typically requires an overnight on the route.

- Grade VI: Two or more days of hard technical climbing.

- Grade VII: Remote big walls climbed in alpine style.

Ice Climbing Ratings

Used for steep snow and alpine ice routes. Technical ice climbing routes are most commonly graded using the WI- scale, for “winter ice.” The current range of grades runs from WI1 to, debatedly, WI13.

In reality, there are very few ice climbers or ice climbs in the world above the WI7-8 grades. Anything above that is highly technical climbing on nearly horizontal overhangs with some form of thin or bad ice.

The W1 grade is for low-angle ice suitable for walking. As the technical grade of an ice climb gets harder, it gets steeper or harder to protect or more tenuous, with fewer resting spots. Steep climbing begins around WI3.

In serious alpine terrain, the WI- rating prefix, which is generally used for seasonal or temporary water ice routes, may be replaced with an AI- prefix for “alpine ice.”

Mixed Climbing

Mixed climbing is a hybrid method in which climbers use a combination of rock and ice climbing tools and techniques to ascend routes with thin or inconsistent ice and snow cover. Climbers use their ice tools and crampons to hook tiny edges and slots in the rock when the ice runs out. This technique is called dry tooling.

Mixed climbing grades are denoted by an M- prefix, and the scale runs from M1 to M15. Routes at the higher end of the scale tend toward overhanging gymnastic climbing with sustained technical dry tooling.

Climbing Grade Conversion

Have you ever traveled to another country only to discover that the climbing routes there use a completely different grading system than what you know? If so, you probably realized that accurately converting climbing grades is crucial for a safe and pleasant experience.

For example, if you climb 5.10d in the United States and encounter a 6c route in Spain, chances are you will have a hard time sending it.

Our converter below enables easy climbing grade conversion between the world’s five most popular grading systems for free climbing.

Note: The tool can take a few seconds to appear below.

Most Popular Conversions

- 7A+ to V-Scale → V7

- 7B to V-Scale → V8

- 7C+ to V-Scale → V10

- 8A to V-Scale → V11

- 8A+ to V-Scale → V12

Climbing Grades FAQs

It can’t be stated often enough that all grades are relative. Climbers should compare themselves to their own baseline and develop their own climbing goals and objectives. Focus on reaching the next grade, and you’ll soon be a good climber.

The answer to this depends mostly on who you ask, but most climbers consider 5.10 or 5.11 (YDS) free climbing the beginning point of difficult, sustained technical climbing with continuously vertical walls.

To climb a V5 problem, a boulderer must be strong enough to make the equivalent of at least one 5.12b (YDS) move. This is considered an expert level of difficulty for roped climbing, so a V5 requires a great amount of strength and technique.