Rusty Reno Interview

Note: this text was originally published by Adam S. on an earlier version of Climbing House.

A Jolly Good Time

By the end of his undergraduate program, R.R. Reno (“Rusty”) was anxious to do some climbing. College in Pennsylvania doesn’t allow for much of that. Sure he’d been on summer trips, but aside from that, he had not been able to really summit anything substantial as of late. So when Alex Lowe called him about a new route in Yosemite, he jumped at the chance. As one of the best free climbers in the world, Rusty’s friend from the days as a Yosemite bum was eyeing a new route on El Cap called Jolly Roger. His friends always seemed to call him when it came time to do the stimulating routes.

This route was no exception. The first ascensionists, Charles Cole and Steve Grossman were known for being conservative with gear placement. They, like Rusty, performed well 40’ above their last piece and their routes exemplified that strength. So when it came time for Rusty to lead pitch six, it was no surprise to see 100’ feet of knobby face climbing paving the way to a bolt that would be the only protection. With Lowe at the belay, Rusty took off and ran it out in typical confident Reno fashion. Knob after knob brought him to the 5.8 mantle to reach the security of the bolt.

He contemplated the mantle, as it turned out to be less trivial than he imagined. Experimenting with various microchips and inconspicuous depressions, he maintained his cool despite looking at a 200’ fall. Finally, Rusty has a little conversation with himself;

“Come on Reno. Make the move. It’s 5.8. Yeah, you haven’t been climbing in a month, but you can’t fall. People don’t fall when their 100’ run out. Just make the move.”

And so it went. High foot, grab the smear, eyeball that bolts only feet away, and tell yourself it will all be over soon. The only problem is that’s not the way it went. Somewhere in the middle of that, a foot slipped or a hand blew and that sent our hero on the ride of his life. He spent the following seconds skating down the smooth granite face of El Cap; 30’, then 40’, then 70’ then 120’. Finally, at the 200’ mark he hit the end of the rope and slammed into the dihedral to his left. Jarred, but conscious, he ascended the rope to inform Alex that he’ll need to lead this pitch. Now, Alex had just recovered from a large fall in Alaska that winter, and recognizing Rusty’s condition, he chuckled and said, “You’re a mess! We’re going down.”

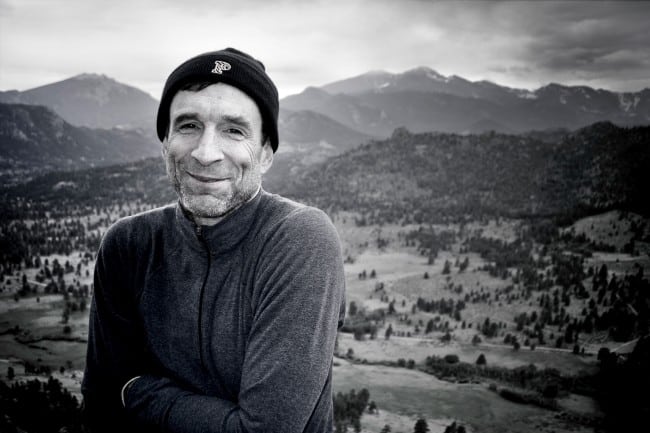

Meet Russell “Rusty” Reno (R.R. Reno), former Yosemite bum, professor, father, husband, and educator to the wide-eyed youth of Omaha’s climbing community. He, fortunately, survived the plunge on Jolly Roger with a few bruised ribs and a sore back. He, of course, spent a couple of days in his tent with a steady supply of Asprin and rest. After those couple of days though, he felt “human again” and he and Charles were back on El Cap. That time it was on Zodiac because he needed the comfort of a route he knew he wouldn’t fall on.

Rusty is nothing short of legendary in these parts. And it’s not only because he survived a 200’ fall. In fact, that story has become subsidiary to the larger constitution of our local icon. He is a friend and patriarch. During our time together, he has been a wealth of knowledge and inspiration, not to mention a matter of fable. In short, Rusty has IT.

In the past five years, we have chipped away at the Reno story bit by bit. However, in the interest of efficiency and carrying on the Yosemite thread, I thought I’d sit down with the man himself to get the full story and see if I can seek out just a little more insight on the world through the Reno looking glass.

The Reno Saga

Rusty was introduced to climbing by his father at age fourteen. His father, who it seems Rusty inherited his determination from, knew not much more about climbing other than that “he wanted to climb pointier and pointier mountains.” And so with his older sister, the Reno clan delved into the vertical world. The first few years amounted to bouncing among the local crags and the Gunks. It’s not hard to imagine how a willful spirit like Rusty’s would catch the climbing bug. So when it came time for his older sister to go to college on the west coast, Rusty was quick to visit after finishing high school. The word in Portland at the time was if you wanted to rock climb, Yosemite was the place to be.

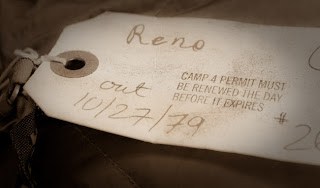

With no real plan, other than to climb, Rusty hitchhiked from Portland to the Valley. He arrived Labor Day weekend with one carabineer, his EBs, harness, and a backpack. The next few months were educational and adventurous, to say the least. His time was spent mastering the climbing craft and exploring the Valley with fellow blossoming Yosemite legends.

Rusty shacked up in the Valley until funds ran dry. This served as an opportunity to return home to Baltimore to visit family and replenish the bank account, thus completing the cycle of the climbing bum lifestyle.

He was back in California in late January, but to his disappointment, there was far much snow on the ground. And so he did what Yosemite Bums do (now). He retired to, the then undiscovered, Joshua Tree. In many ways, Joshua Tree was the anti-Yosemite. Where the Valley was the epicenter of American climbing in the ’70s and ’80s, Joshua Tree was still a local secret. In Yosemite, it was not uncommon to meet climbers from around the world. Rusty even had the pleasure of meeting Reinhold Karl who had come to conquer El Capitan. Joshua Tree was inhabited by the Southern California crew of the ’80s. Names like Bachar, Cole, and Long were likely to be your partners at Joshua Tree.

Somewhere around a year after starting his expedition, his focus started to shift. Bill Denz and Murray Judge, who were to Rusty ”incalculably old”, had approached him to inquire about his interest in a trip to Patagonia. Still having that college acceptance letter that he had received last fall rattling around in the back of his head, he simply replied, “I’m kinda planning on going to college.”

And so he momentarily retired from the life of a dirtbag to return to Philadelphia for school. Unfortunately, that was short-lived, as he was more drawn to pursue that at which he excelled; namely climbing. After a couple of semesters, he had stepped back on the road, backpack slung, and thumb extended, bound for the West. The next few months included traveling among the Canadian Rockies, the Tetons, a job on an oil rig in Wyoming, and of course Yosemite. Although it seems that settling back into the Valley enlightened him of the hastily-conceived decision to leave school. This realization was then followed by a shameful call to the dean expressing his regret and pleading his case to return.

Right about now is usually where the story ends. Our hero has his fun, but eventually, life catches up to him and he’s forced to move on. He goes to school, gets a job, has kids, and grows old. We all know this presupposition of the climbing bum lifestyle. But apparently, this social construct did not suit Rusty. His years as an undergrad were lean with respect to climbing. Three sports, study abroad in Deutschland, and influential classmates seemed to keep his head in school. Additionally, the distance between him and suitable destinations had grown beyond its practical limit. That’s not to say that as soon as classes ended in the spring, he wasn’t back on the road.

However, his graduate school years saw a pivotal moment in his climbing career. It’s easy sometimes to place boundaries on ourselves. Living within life’s paradigms or dismissing opportunities is a sure formula for disappointment. Some conversation with his friend Charles, who had been commuting six to seven hours weekend after weekend between Redlands and Yosemite, seriously opened his eyes to the possibilities of climbing on his side of the country. Charles’s six-hour commute really put Rusty’s three-hour commute to his local area in perspective. Furthermore, he realized there was much that could be gained from weekend trips and even more to be lost by ignoring these opportunities. So with a revised focus, he began a period of “slash and burn” trips to destinations that until recently seemed so far away and he continued at this pace through the milestones that historically marked the end of this lifestyle.

Since his reformation, Rusty has built a proud climbing career. He has climbed all around the United States and Europe. He has a handful of first ascents in Yosemite Valley and has become an accomplished and respected ice climber and alpinist in addition to his prowess as a rock climber. I could occupy a short novel chronicling his stories, but stories like his are so much better in person. I would encourage anyone who has the opportunity to hear them from Rusty to seize it.

Now, during his years in graduate school and beyond, allowing climbing to occupy so much time could be perceived as a bit selfish, but his particular anecdote illustrates a great point. In all aspects of life, from climbing to careers, we face boundaries, oftentimes ones that are self-imposed. In this case, the limitation was only allowing a climbing trip to fit in a strict definition. Another example is the climber who quits as life “catches up to him.” However, Rusty speculates that those who limit the scope of their effort in this way are trying to escape a lifestyle that no longer interests them, thus the self-imposed limitations.

Conversely, it is by no means improbable to be able to maintain the balance for those who wish to continue. The keyword, of course, is balance. Hardly anyone will be a 5.14 climber, the CEO of their own company, and maintain healthy family relationships, but the secret is to find the balance of all the things that are important, realizing (and this is the key) that there will be sacrifices. Suffice to say this balance is different for everyone.

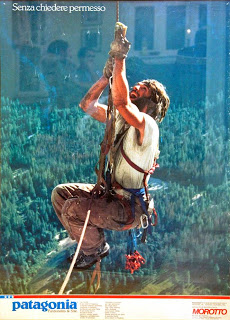

With some experimentation, Rusty found his balance. His time these days is split between the classroom, his study, his bicycle, his family, and climbing. He is to the point where his drive to remain in climbing is fading precipitously, but what keeps him in it? Like most, part of it is the camaraderie. His wife, Julianna, once likened being a climber to being a member of a fraternity. Someone like Rusty knows someone nearly everywhere he climbs. I am reminded of a time we were driving out of Eldorado Canyon SP when by chance one of Rusty’s former friends from Yosemite was having a yard sale in Eldorado Springs, complete with a print of Rusty hanging from a fixed-line 2000’ feet up El Cap.

Another element of the climbing’s magnetism is the freedom of movement, the “ballet” on rock as Rusty puts it. Throughout the interview, Rusty cited a quote of Aristotle’s that says “Happiness is unimpeded activity.” Picture Jordan in the closing seconds of game 7 in the NBA Finals or Mario Andretti in the Indy 500. It’s that feeling of being able to fully give yourself to something for that moment. To be on the edge, but so focused and in control of yourself. For Rusty, and I think many of us, it is rewarding to push yourself physically while being forced to maintain the mental acuity required to manipulate gear, route find, but most importantly climb.

The People of Yosemite

In the spirit of the fellowship of climbers that keeps so many of us doing this inane activity, I would be remiss, not to mention the faces of Yosemite that left an impression of Rusty. Contrary to what you may think, the most colorful individuals of Camp 4 weren’t avid climbers. Something about regular drug use and climbing doesn’t mix. However, that’s not to say there were a few memorable personalities among the rock junkies.

Opposite the hippies and casual climbers were those, who were driven, at times compelled, to be on the rock. About the compulsion, names like John “Yabo,” Yablonsky, Walt Shipley, and John Bachar come to mind. This compulsion was apparent to Rusty, even as a teen. Then you have the larger-than-life personality of John Long, who “is the way he writes.”

The senior statesman of Camp 4 was Jim Bridwell, a.k.a. the Admiral. In his mid 30’s he assumed the role of “Leader of the Bums.” Perhaps one of the most memorable characters for Rusty was Russ Walling, more affectionately referred to as the Fish. Russ sported a VW bus adorned with troll dolls and was featured in Rolling Stone. By Rusty’s account, he was “brilliant, creative, and funny.” Think Lucas Marshall.

One of the cold fall days found Rusty shacked up at the coffee shop with some of these folks. After three hundred straight days of climbing, including 18 El Cap ascents, Dale Bard had caught Rusty’s attention. I think he was drawn similar qualities of the climber in himself. He asked to talk with him a while, to which Dale Responded, “I’ll talk about anything, as long as it’s not climbing.” Looking back, Rusty considers this a vital lesson.

The Myth of the Adrenaline Junkie

If I had to describe the way Rusty climbs, it would be confident and deliberate. If I had to describe the way Rusty communicates, it would be confident and deliberate. It is his job, after all. So when I asked him a question he didn’t have a swift, comprehensive answer to, I was particularly interested to hear what he had to say. The question had to do with whether or not he had ever gone too far or regretted a decision.

After a long pause, he came up with an experience he had in Joshua Tree climbing with Charles. He hadn’t been climbing in a few months, and he and Charles were headed to J Tree for a little reintroduction. They arrived late in the day, but wanting to get in some vertical mileage, Charles had suggested they free solo Walk on the Wild Side (5.8). This friction route was really the only notably tall climb in the park. Rusty obliged, but upon reaching the crux at 150,’ he thought to himself, “What the hell am I doing here.”

First, he is not fundamentally opposed to free soloing. He has not done much, but enough to know what it’s about. He’s also done routes in Tuolomne that are 100’ to the first bolt, basically free soloing. But if you’re comfortable at the grade and sharp mentally, soloing isn’t intrinsically dangerous. His regret from the Joshua Tree experience seemed to stem from walking into a situation unprepared, making it dangerous.

It’s the misconception that leads to the categorization of climbers as adrenaline junkies. I cite Rusty’s enjoyment in climbing from self-control in stressful situations like that on Jolly Roger. It’s essentially the polar opposite of an adrenaline rush. It’s the ability to control the primitive compulsion that can lead to panic and make yourself accomplish feats you didn’t know were possible.

Parting Shot

R.R. Reno

“[Climbing] is not as important as it seems. Don’t overestimate it, and if you don’t, you’ll probably enjoy it longer because you won’t make it play a role in your life that it can’t really play. It can’t be like religion. It’s a temptation to confuse the intense experience of climbing with something that’s more life fulfilling. I think the people who did that ended up unhappy.”

It’s undoubtedly the salient nugget of wisdom in this article. It was Rusty’s interpretation of what Dale Bard told him as a young climber. Climbing is one of those unusually addicting activities, which makes its participant susceptible to placing a higher worth on it than is appropriate. The climbers who have not fallen into this trap, it turns out, tend to enjoy their sport more in the long run.

Take Alex Lowe. He is “one of the, if not the great climber,” of Rusty’s generation. By Rusty’s account, he was far more passionate about climbing than himself and many others in the climbing community. He loved climbing. He spent time as a guide, which does have its rewards in the realm of teaching, but it seemed that it also satiated his strong desire to be in the mountains. However, the important concept to remember is that his passion “had a context that was more than just climbing experiences.” He was married, had children, and earned a Master’s degree in environmental engineering. In his time away from climbing, he explored the mountains through cross-country ski racing.

All of this is part of the reason he was so well-liked, in addition to his other personal strengths. “Those good qualities were enriched because he didn’t make rock climbing the sole focus of his identity to the exclusion of those things.” Despite their level of fulfillment, the physical and mental pursuits of climbing have a limit to their enjoyment. It is important to understand what climbing is “for” and that, in the end, will help you get the most out of it.

This is something that I see in Rusty. I briefly mentioned at the beginning of this article that Rusty has IT. A few of us have spent some time talking about this, but we haven’t quite pinned down what it is that we admire so much about him. The ideas presented here are the closest I have come so far. What we admire in Rusty is indeed his strength as a climber, amiable demeanor, and volumes of wisdom and experience. But what underscores all of that is the fulfillment he gets out of life by having “everything in its right place.” This is what makes him Rusty Reno