Onsight vs. Flash vs. Redpoint: The Definitive Guide (2024)

Published on: 07/07/2023

Introduction

If you’re just diving into the world of rock climbing, you might be struggling a bit with all the terminology. Climbing is notorious for its heavy use of jargon. Three terms in particular that are often confused are onsight, flash, and redpoint. Each refers to a different way of completing a free climb.

As a new climber, you’re probably just worried about getting to the top. However, when you delve deeper into the sport, climbing ethics will probably become increasingly important. As a result, learning and understanding the difference between an onsight, flash, and redpoint in climbing is key to progressing as a climber.

From Aid to Free Climbing

To understand the difference between a redpoint ascent, an onsight, and a flash, we have to go back to climbing’s roots.

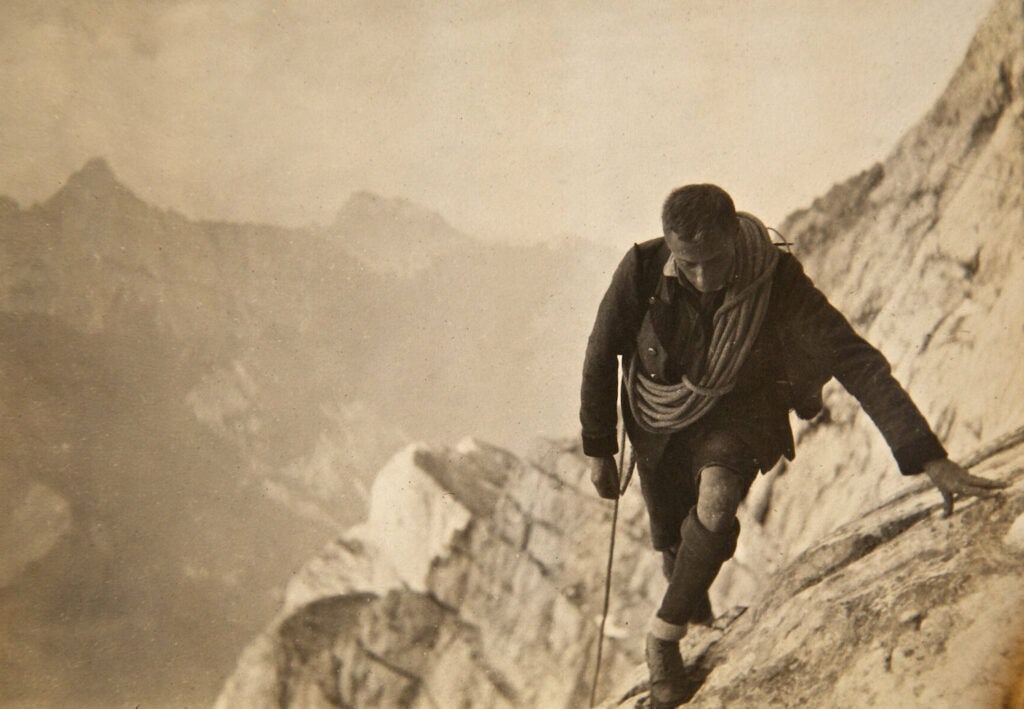

Originally, climbers ascended walls using any means necessary, pulling on pitons, beaks, and ladders to gain ground. There was no trad climbing or speed climbing or bouldering. It was all just “climbing” and you got up the wall however you could.

In 1911, however, Austrian climber Paul Preuss (1) advocated for a distinction between using mechanical devices to progress upwards and using solely the power of one’s own body. To him, the former discipline became “aid climbing” and the latter something entirely new: “free climbing.”

In short, free climbing is any type of climbing that sees the climber ascend a formation entirely under their own power, using only the rock’s natural features. Unlike aiding, where gear is used to ascend the wall, climbing routes free means using gear only to protect the climber if they fall.

Free climbing didn’t become widely popular until the latter half of the 20th century, but today it’s the default style of rock climbing, and what most people think of when they think of the sport of climbing. An onsight, a redpoint, and a flash are all ways a climber can complete a free climb, be it a sport route or trad.

Redpoint

Origin and Definition

A redpoint is the most basic form of free climbing ascent. A climber achieves a redpoint in climbing when they reach the top of a route without falling during the ascent.

A redpoint can be achieved at any point in time, and unlike onsights or flashes (see below), prior information or attempts do not disclude a climber from earning a redpoint. As long as you successfully climb a route cleanly, without falling, you’ve nabbed a redpoint.

The term redpoint originated in the mid-1970s as a translation of the German word Rotpunkt. Kurt Albert (2), one of Germany’s strongest climbers and a pioneer of hard sport climbing around the world, would mark fixed metal pitons with a red “X” on any route he was working in the Frankenjura.

This helped him avoid the gear while he was going for a free ascent. Once Albert made the first ascent of a given project without a fall, he would paint a red circle (a “Roter Punkt” or “red dot/red point”) at its base.

This red dot indicated that the route had successfully been free climbed (as many of the routes Albert was working were originally aid climbs). At this time, Albert also laid down the rules that to earn a “redpoint.” If climbers fall, they must lower to the ground, pull the rope free, and restart.

Rules and Ethics

As noted above, a successful redpoint only occurs if the climber is climbing on lead (not top rope), and they do not take any falls during the ascent. If a fall is taken, the climber must return to the ground, pull their rope, and begin the entire climb over again. Similarly, the climber isn’t allowed to hang on the rope and make repeated attempts at a section of the route (“hangdogging”) during their redpoint attempt.

Stickclipping

Some climbers (including this author) also consider the practice of “stickclipping” to disqualify a redpoint. Stickclipping refers to clipping the climber’s rope through the first bolt in advance, essentially allowing them to top rope the route to the bolt, then lead from that point.

This practice prevents dangerous falls at the outset of the route, before the climber is on belay. However, it reduces the strength and stamina needed to climb the route, as the climber no longer has to place or clip their first quickdraw while on the wall.

Related Concepts

Pinkpoint

Pinkpointing isn’t something that’s really used anymore, but originally, earning a pinkpoint was a slight variation on a redpoint. Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, redpointing specifically meant freeing an entire route without pre-placing all the quickdraws on the wall. A pinkpoint, on the other hand, referred to freeing a climb with draws already in place.

The pinkpoint has generally died out, probably because of the popular opinion that sport climbing is more about testing one’s physical fitness, not placing gear. Most high-end sport climbers today, folks sending hard 5.14s and 5.15s, tackle their redpoints with quickdraws pre-placed to maximize potential and increase safety.

However, the difficulty gap between carrying, placing, and clipping quickdraws and having all the draws pre-placed in advance is often considerable, especially on longer climbs.

Even the added weight of carrying a dozen or so quickdraws up a route can affect your stamina and endurance. So some climbers do still appreciate the distinction between what constitutes a pinkpoint and redpoint.

Headpoint

Headpointing is when a climber rehearses a route on top rope before going for the redpoint on the sharp end. A climber may also rappel in and examine the moves, or play with a few sections while jugging a line.

A climber would usually headpoint on a traditional route with sketchy or limited gear placements, but headpointing can also be used on runout (or otherwise dangerous) sport climbs. The process of working the route on top rope before a send is the “headpointing,” although the eventual send (if it occurs) is still considered a redpoint.

Redpoint Crux

The term redpoint crux refers specifically to a section of a route that will give climbers difficulty on the redpoint attempt, as opposed to a general crux. The latter may objectively be the hardest sequence of moves on the route, but the former (usually due to a position higher on the wall) is the more formidable obstacle when the route is climbed in its entirety

Onsight vs. Flash

Onsighting (or “on sighting”) and flashing are both types of redpointing, but they are exclusionary. Unlike a redpoint, climbers only have a single chance to earn an on-sight or flash, because both must be completed in the climber’s first attempt on the route.

The Onsight

To climb a route onsight, the climber must reach the top of the route without falling on their first attempt, without any prior knowledge of the route. This could be beta from other climbers, detailed descriptions in guidebooks, or tips gleaned from watching another climber try the route.

You must climb the route first go in the purest form, by walking up to the wall and tackling it completely “on sight.”

Again, the exact definitions of climbing a route onsight can vary slightly based on who you ask, but the following are widely accepted forms of prior information:

- Watching another climber on the route (either in person on video)

- Receiving beta on the route from other climbers or guidebooks

- Having climbed any sections of the route in the past

- Having inspected the holds on the route in any way in the past (such as while rappelling, jugging, or even examining lower holds from the ground).

Ultimately, onsighting ethics depend largely on a climber’s personal opinion (see “When Onsighting Becomes Flashing” below). You can take it as deep as you’d like. To hardcore purists, many, many stipulations can disqualify an onsight, including pre-placed gear. More on that below.

The Flash

To earn a flash, a climber must send the route on their first attempt, without falling. The difference between an onsight and a flash is the “prior knowledge” stipulation. Flashing doesn’t exclude prior knowledge. So essentially, an onsight is simply a higher form of a flash (and the latter is a higher form of a redpoint).

You can have as much info about the route as you want. If you send it on your first attempt, it’s still flashing the climb. Also, you can watch videos of other climbers on the route, scoping their body positioning and movement. Asking climbers who’ve been on the route for beta, such as key holds, rests, and sequences, is also allowed.

There are a few things that would disqualify a flash that may not be obvious, such as having previously worked out sections of the route. (For example, if you climbed a neighboring route that shares moves with this climb.)

Rappelling or jugging the route in advance and inspecting the holds would also be considered a faux pas if you intend to claim a flash. Setting up an identical array of handholds and footholds in a gym, and training on that clone route to prepare for the send, would also constitute bad form (if you were to claim flashing).

When Onsighting Becomes Flashing

The differences between onsighting and flashing can be somewhat murky, and minutiae often vary between climbers. For example, when onsighting some climbers consider it acceptable to read a short route description in a guidebook. Others would consider this “prior information” and make the first ascent a flash, not an onsight.

Sometimes it’s best examined on a case-by-case basis. A simple description that simply delineates the main feature of the route (i.e. Follow the prominent flake to a large roof”) is probably not disqualifying. An overly-detailed description (i.e. “Be sure to match left after the fourth bolt, and don’t miss the undercling below the crux”) is likely disqualifying of an onsight.

Photos in a guidebook are also case-by-case. If the photo just shows the climb, that’s one thing, but if it is a close-up of the crux sequence or it shows a climber working moves on the route, that’s another.

Other purists maintain that for a true onsight, there must be no gear placements on the wall, such as quickdraws or even permadraws at the anchors (or pre-placed cams and nuts, if traditional climbing).

Others go even further, saying that if the climber even knows the route’s grade, this is also “prior knowledge” because they now know the difficulty to expect on the wall.

It’s Up to You

This might all seem quite nuanced, and maybe even a bit anal-retentive. But luckily, we all get to make our own rules when we climb. Unless you’re a professional climber being paid for your sends, nobody is going to be policing you about your definition of an onsight or a flash. It doesn’t matter. Safety is what’s most important, and whatever makes sense to you is what you should abide by.

Just be honest in how you represent your ascents. If you’re walking around bragging about how you sent a rock climb onsight, even though you watched a dozen videos of other climbers on the route and rehearsed the moves on top rope for hours in advance… Well, then you might raise a few eyebrows.

Legendary Climbs

In the years since the German rotpunkt and Kurt Albert, there have been numerous developments in the sport of climbing. The world’s hardest climbs are lightyears away from what they were in the 1970s. When Albert was on sighting climbs in the Frankenjura, the hardest routes in the world were only 5.12c (7b+) to 5.12d (7c).

Today, several women, such as Angela Eiter, Julia Chanourdie, and Laura Rogora, have redpointed up to 5.15b (9b). Two men have even redpointed even harder routes, proposed 5.15ds (though both routes, Adam Ondra’s Silence and Seb Bouin’s DNA, have not been repeated, and thus are not confirmed at the grade).

Janja Garnbret, one of the world’s leading female climbers both on plastic and on rock, has onsighted several routes at 5.14b (8c). Top male sport climber Alex Megos has onsighted 5.14d (9a+), first with Estado Critico, and Ondra has even flashed a 5.15a (9a+) sport climb with Super Crackinette.

With the advent of the internet, the distinction between an onsight and a flash has been increasingly harder to verify. Route beta and videos are widely shared and available. On the cutting edge, the biggest focus remains on redpointing. Both 5.15d lines, Silence and DNA, remain unrepeated (as noted above), and these two projects are some of the most sought-after sends in the world of sport climbing.

Garnbret has also been seen working La Dura Dura (5.15c) in Spain, and if she earns a redpoint, it would be a first in the history of women’s climb. However, in recent months, most of her social media updates have focused on the IFSC competition scene, where she regularly tops the ranks.

References

Paul Preuss

Wikipedia (retrieved on 07/07/2023)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Preuss_(climber)

Kurt Albert

Wikipedia (retrieved on 07/07/2023)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurt_Albert