Barbie on the Rocks: How Climbing Might Look in Barbie’s World

By Chris Kalman

Published on: 08/11/2023

Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past few weeks (which, admittedly, may apply to climbers disproportionately), you’ve probably seen—or at least heard of—the Barbie movie. Released on July 21, 2023, the film endeavors to envision a world ruled by Barbies. That is, one in which the power, privilege, and prestige is held predominantly by women, not men.

After seeing the movie with my wife, I’ve found myself wondering: What would the sport, lifestyle, industry, and general community of climbing look like in Barbieland?

Here are ten things I think would be dramatically different—and probably better.

1. Most of the climbing companies would have women founders.

Patagonia. The North Face. Mountain Hardwear. Outdoor Research. Black Diamond. Eddie Bauer. Arc’Teryx. Marmot. Petzl. La Sportiva. Scarpa. Adidas. Metolius. What do all these companies have in common? Aside from making climbing equipment, they were all founded by men. In fact, it is difficult to find a climbing company that was founded by a woman, though some examples of women-owned businesses do exist.

In Barbieland, Patagonia would have been founded by Malinda Chouinard, not Yvon. The North Face would have been founded by Kristine McDivitt Tompkins (who actually ran Patagonia for a while, as well as, recently, Rose Marcario), not Doug. And women like Abby Dionne of Coral Cliffs (the country’s only Black queer climbing gym owner) and Kristin Horowitz of The Pad Climbing Gym (the Chamber of Commerce’s 2022 Women-Owned Business of the Year) would be the rule, not the exception to it.

2. The climbing media would center women instead of men.

Following the money from the gear companies to the media where they advertise, it’s no surprise that said media has a patriarchal bent to it. That’s why we have affinity groups and organizations like No Man’s Land Film Festival. What if our biggest film festivals—Banff, Telluride, and 5 Point—featured predominantly women filmmakers and protagonists, and we had affinity spaces for men instead? Imagine a world that necessitated the creation of a Man’s Land Film Festival (er… maybe don’t imagine that).

Climbing writing is just as male-dominated. Consider Summit Magazine, whose founders—Jean Crenshaw and Helen Kilness—hid their identities on the masthead because they were “concerned that no one would buy the magazine if readers knew it was run by women,” as Katie Ives points out.

In Barbieland, that would not have been necessary. Imagine a world where the top hit for a google search for “greatest climbing novels ever” wasn’t a top 10 list featuring one (that’s right, one) female author. A world where Katie Ives reigned supreme over Jon Krakauer; Steph Davis over John Long; Bernadette McDonald over David Roberts; Kathy Karlo over Chris Kalous.

3. The most celebrated climbs would be ones put up by women.

With women at the helm in the media, we’d be seeing very different climbs (and climbers) getting all the coverage. For example, Beth Rodden climbing Meltdown back in 2008 would have been a watershed moment for the sport. At 5.14c, it was one of the hardest pitches of trad in the world at the time, if not the hardest. But neither Meltdown nor Rodden got the attention they deserved—probably because most men wrote the climb off as irrelevant since it suited smaller fingers (read, women’s fingers), instead of their own grubby digits.

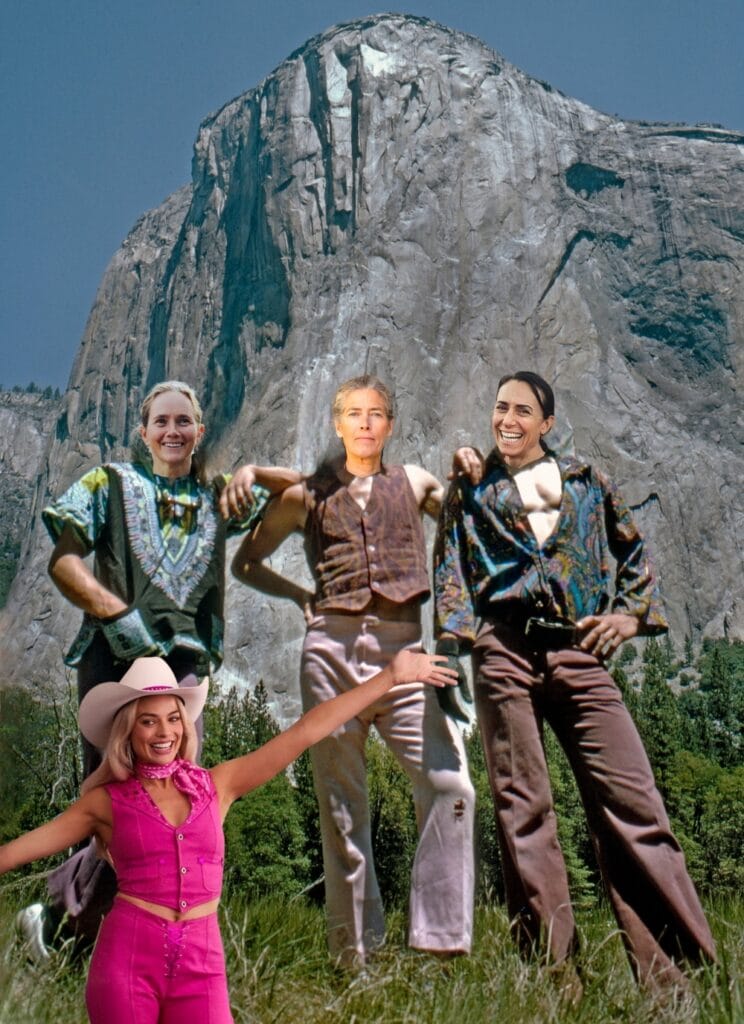

It took ten years before a man was finally able to free Meltdown. Ten years. Few climbs of such notoriety and ease of access ever resist a repeat for so long. Another one? The Nose of El Capitan—also first freed by a woman, the indomitable Lynn Hill—sat unrepeated for 13 years before it was freed again by Rodden (and the Ken she was hanging out with at that time). In Barbieland, it would be men trying to repeat women-established routes that didn’t suit their natural anatomy and skillset; not vice versa.

4. The strongest climbers in the world would be women.

When Lynn Hill claimed the first free ascent of the Nose, she could have been (and should have been) crowned the strongest/best/most talented climber in the world. Of course, she wasn’t. By most accounts, that honorific still belonged to Wolfgang Gullich, who had climbed the 5.14d, Action Directe, two years prior. Hill’s masterpiece required 1,000 meters of laser-focused footwork, technique, and body tension. Gullich’s magnum opus was 15 meters long. Even though Action Directe is far shorter, and was repeated a mere four years later (remember: The Nose was not freed again for 13 years), it is still considered the “harder” route. Why? Because of what the male-dominated sport of climbing privileges in terms of difficulty (e.g., wild campusing over careful footwork). But judging by the numbers, The Nose is actually the harder climb to repeat.

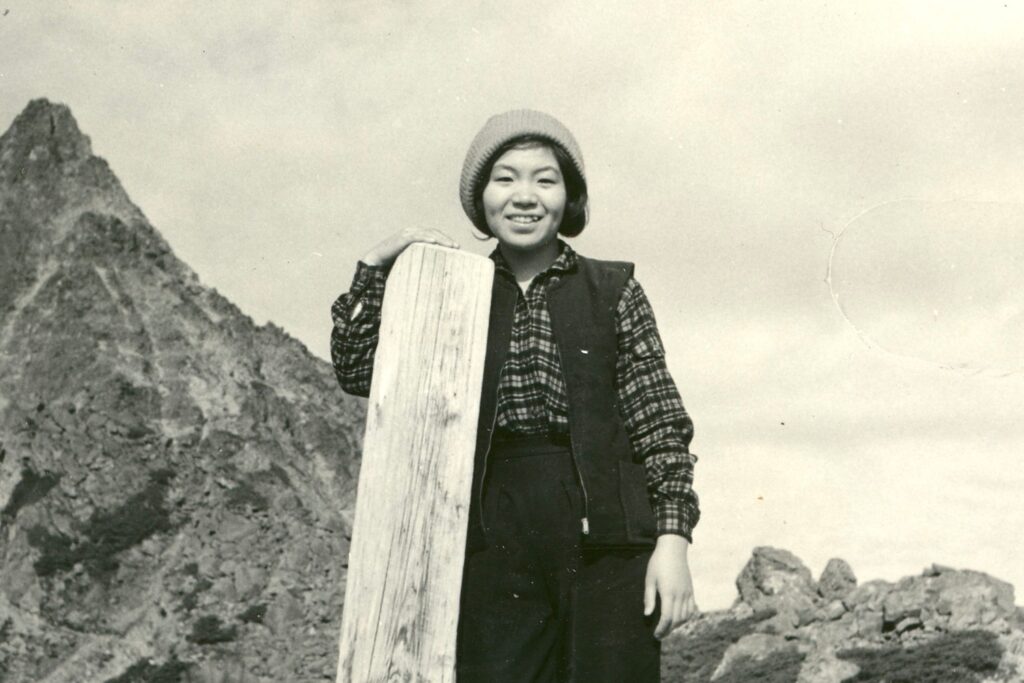

Of course, nobody in Barbieland would have been surprised if Lynn Hill had been called the strongest climber in the world. She would have been preceded by a proud lineage of other women who had been similarly queened—from the likes of Junko Tabei, Wanda Rutkiewicz, and Alison Hargreaves, to Catherine Destivelle, Josune Bereziartu, and Katie Brown. Their accomplishments (Hargreaves being the first person—male or female—to solo the six great north faces of the Alps in a single season, for example), would not be senselessly overshadowed by those of their male counterparts.

5. The most famous climbers in the world would be women.

This may go without saying, as it should follow as a natural corollary from the previous point. But of course, it’s still hard to imagine, isn’t it? Go ahead—picture a world where Nina Williams (212K instagram followers) is more famous than Alex Honnold (2.6M instagram followers). Where Rodden is better known than Caldwell. Garnbret over Ondra. Shiraishi over Sharma. It’s difficult to envision—but not because women climbers are any less strong, driven, skillful, compelling, interesting, complex, or memorable characters.

In Barbieland, great male climbers would still be recognized and honored for their achievements. But the real top dogs would all be women. And there’d really be nothing surprising about that, since it would tend to take men much longer than women to repeat all the hardest routes in the world—routes that, again, would better suit women climbers.

6. Climbing gyms would feel like a much safer place.

In 2016, Flash Foxy conducted a survey exploring how gender affects one’s experience at the climbing gym. “Sixty-four percent of women who took the survey said they felt uncomfortable, insulted, or dismissed at some point during their training, as opposed to 29 percent of men.” So writes Shelma Jun, founder of Flash Foxy and creator of the Women’s Climbing Festival.

“65 percent of women said they had experienced microaggressions… 39 percent of women complained of unwanted staring, more than double the percentage reported by men… In other words, just because most women don’t experience blatant, aggressive sexual harassment at their climbing gyms, doesn’t mean it’s not there in the form of condescension or unwanted flirtation.”

If Flash Foxy were to conduct the survey again, they might consider polling respondents on receiving unsolicited mansplaining and beta. At least according to this Reddit forum. Of course, in Barbieland, the men would be too busy “beaching” to teach women how to do things they already knew, like how to tie figure-8 knots and hike Ken’s projects.

7. There’d be no body shaming, bullying, or sexist route names.

Of course, nobody in Barbieland would ever dream of naming a route something like “Astride my Indian Queen.” But as Amanda Loudin pointed out for The Lily (an imprint of The Washington Post), names like that are painfully common in the male-dominated climbing world. Equally implausible would be an asinine debacle where a male pro climber would create and use an anonymous instagram account to publicly body-shame his female counterpart.

Sure, women can be cruel to women, too—at least in our patriarchal civilization. But it’s Barbieland we’re picturing here—a place where women have one another’s backs. Imagine the impact it would have on future generations of climbers not to be constantly inundated with misogynistic route names, social media bullying, and other forms of hate and violence.

8. Climbing wouldn’t be rife with eating disorders.

Speaking of body shaming, if climbing existed in Barbie’s world, it probably wouldn’t be a magnet for eating disorders. As Caroline Treadway so staggeringly portrayed in her 2021 film, Light, disordered eating and body dysmorphia are omnipresent at the highest echelons of our sport. While this issue does affect men as well, it is clear from the film that it is a struggle women climbers—like bouldering phenom and photography savant, Angie Payne—face disproportionately.

In Barbieland, a climber would be appreciated and celebrated no matter what their body looked like. Everyone is respected in Barbieland, regardless of their profession, skin color, or weight. What if the climbing world could say the same?

9. The majority of climbers would be women, not men.

With all of the above changes taken into consideration, it would be no surprise to see far more women climbing in Barbieland than men. When Barbies saw climbing, they’d see a sport that placed women front and center, not on the sidelines like so many discarded and unwanted Ken dolls. Unfortunately, that’s not how it works in the real world.

In 2019, the American Alpine Club (AAC) released a landmark study of climbing in America entitled the State of Climbing report. Among the report’s findings were that only 41% of climbers—and a mere 27% of the AAC’s own members—identified as female. As bell hooks said, “representation is a crucial location of struggle for any exploited and oppressed people asserting subjectivity and decolonization of the mind.” Climbing in the real world has a major representation problem (and it’s not just a gender issue, by the way).

10. This article would have been written by a woman.

Am I, as a man, contributing to the problem by writing this article? Shouldn’t a woman have written it instead? I think interesting arguments can be made either way—but right or wrong, if this was Barbieland, of course this article would have been written by a woman. All the cards would be stacked in Barbie’s favor. All the advantages, privileges, and systemic forms of discrimination would favor Barbies, not a Ken like me.

In this way, Barbie provides a compelling perspective through which we can see misogyny and patriarchy at work. And racism, classism, ableism and other forms of oppression, as the film attempts to address. Because none of these forms of discrimination or oppression exists in a vacuum, and intersectionality is just as (or even more) important in the climbing world as it is in Barbieland.

The devastating effects of patriarchy, and toxic masculinity, are there in plain sight anywhere you look—whether you turn your gaze toward the climbing world, Hollywood, or politics in the United States of America. All you have to do to see them is imagine the world we know, but Barbie-ified. Flip the script. Turn the tables. Who would have thought that a doll made for little girls could provide such a powerful tool for dismantling one of the world’s oldest systems of oppression? Maybe climbing—a sport, if not a toy—can be an equally potent way to achieve the same goal.