Interview with Route Setter Dom Arcana of The Refuge, Las Vegas

Published on: 08/20/2023

Climbing House editor-at-large Owen Clarke speaks with Dom Arcana, a leading route setter at one of America’s most well-known bouldering gyms, The Refuge.

By Owen Clarke

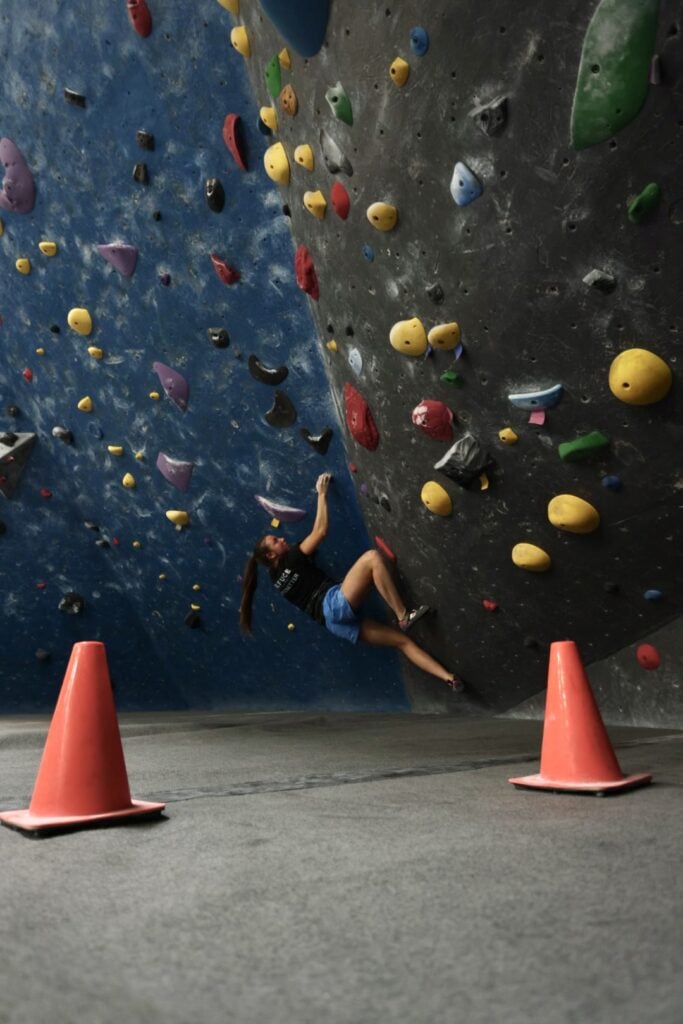

In the vast pantheon of American climbing gyms, one of the names that often comes up is The Refuge. The Refuge is a small bouldering and training gym in Las Vegas, Nevada—the hometown of some of the strongest figures in American climbing, from Joe Kinder to Jonathan Siegrist to Alex Honnold.

The Refuge was recently ranked among the seven best bouldering gyms in the United States by Climbing magazine’s former longtime editor, Matt Samet, and a big part of its this revolved around its setting. “The setting is consistently excellent,” commented Siegrist. “They do an awesome job of setting creative but not overly comp-style problems across the whole grade range. The setting crew pays attention to detail and aims for ‘outdoor-influenced’ difficulty in a very refreshing way.”

When I first moved part-time to Las Vegas several years ago, I spoke with Molly Mitchell and a few other strong climbers I trust about where to come to train, and all of them recommended The Refuge for that same reason—the route setting.

So last week, I took the time to chat with one of the gym’s setters, Dom Arcana, and learn what setting at the Refuge is all about.

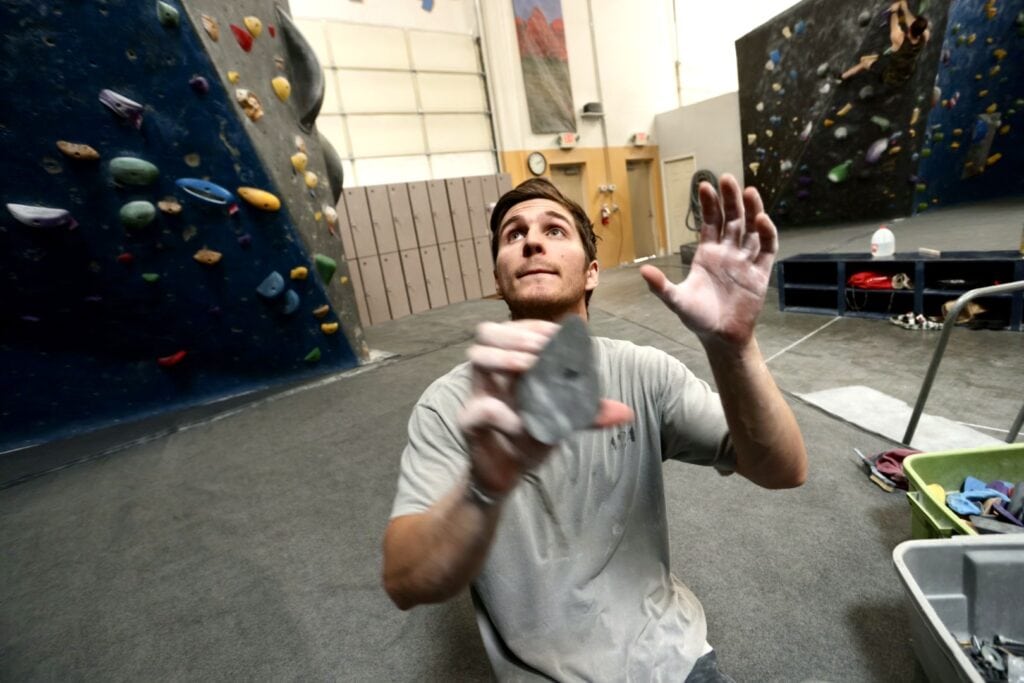

Born and raised in Las Vegas, the 27-year-old began climbing in his late teens, and started setting for the gym in the early days of the COVID pandemic. Today, he’s a leading member of their setting crew and coaches the gym’s youth team. He’s also founded his own apparel line, “Soft Climbing Club,” which has become something of a ubiquitous uniform for Vegas climbers in recent months.

I spoke with Arcana to learn more about the art of setting good boulder problems and what life is like as a route setter. Read on for our full interview.

So Dom, how does one get into route setting? How did you transition from climbing problems into crafting them, and what inspired you to do so?

I always enjoyed watching the setters here when I was just a recreational climber. And like a lot of other people who just started getting into climbing, I was really into watching everything I could find on YouTube. At the time, the Eric Karlsson channel was the biggest YouTube channel for climbing. I was so in love with their setting videos, especially. They were my biggest inspiration.

And over time, I just started becoming closer friends with the people that worked here at the gym, the other setters, the management, everyone. When COVID happened, this gym shut down and I started helping out around the place. Once it reopened, I slid my way in. It’s always hard to get into route setting. I was just lucky.

How do you go about setting a problem? What’s the first step?

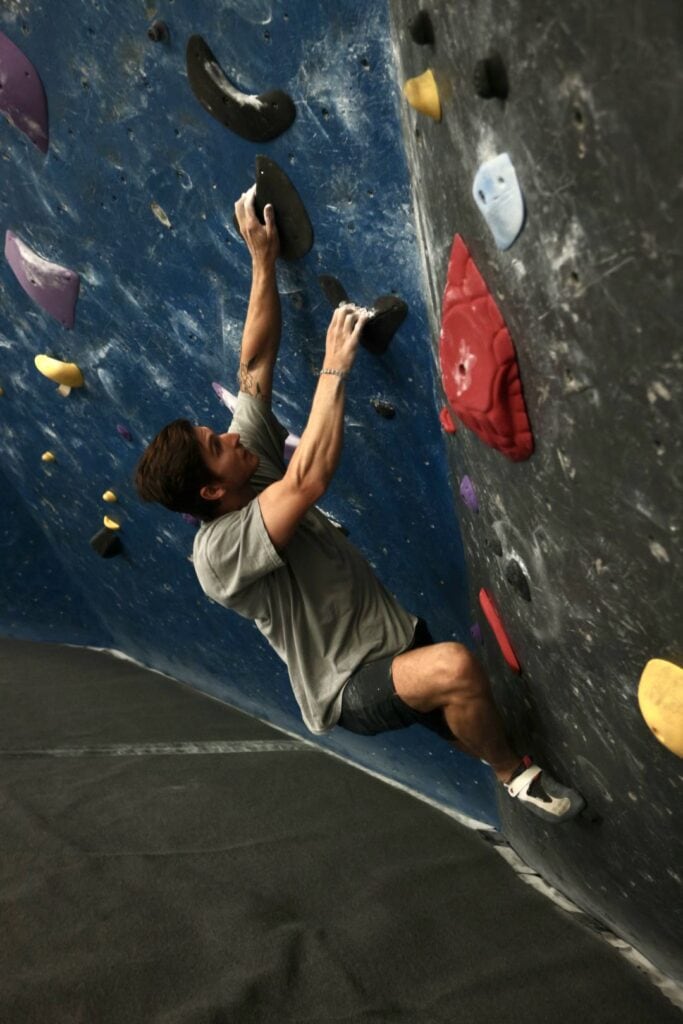

We strip all our holds first. We set one section at a time, so we’ll strip one section of wall per week. First, if I have the time to think about a big vision for one specific boulder, I’ll get a couple of volumes involved. Starting with [those big volumes] gives you a good base to work from.

Once I’ve got a couple of volumes involved for the big picture, I’ll start thinking of a sequence that works with those [volumes]. It’s always different with any specific climb. On some, I’ll put a crux in the middle, make sure the crux works, then work down or up from there. Other times, we put the start holds on and see where it goes.

It’s a very free-form process. But it’s dependent on how many routes are already on the wall, the existing holds you have to work around. It also depends on the size of the holds you want to use, and how feature-heavy they are. Like if you’re using macros instead of tiny crimps, your space is going to be way different.

How often does your team set new problems, and how many are there in total?

Every week we set a new section of wall, and we have a seven to eight-week rotation. So every seven or eight weeks, we reset the entire gym. There are probably 12 to 20+ problems per section, but it varies.

You mentioned setting the crux first and working from there. Is there a conscious decision to set cruxes lower on the wall for safety reasons?

Sure. Particularly if I’m setting a high-commitment jump or swing, I’d rather that be right off the ground for safety reasons. Also if the wall is flatter, like if you’re setting on a slab or just a more vertical wall, you don’t want to have a high fall chance. You don’t want to set low percentage moves when there’s something really big below the problem…

Every now and then there are going to be higher commitment moves higher on the wall, but for the most part, you want those to be set low or middle, to keep people moving.

The process of setting on a slab compared to a cave compared to a vertical wall… Does it differ? Or do you follow the same protocol?

Pretty much. I wouldn’t say there’s anything drastically different about setting a different wall. They all follow the same process. Some are harder than others, like our visor [a fully horizontal, overhung cave wall].

Think about an overhanging wall, if you unfold it and put it straight, it’s actually twice as tall as a normal wall. So the number of moves you’re putting into our visor versus any other wall is usually twice as many. So the time effort is way different for some sections.

The Refuge is known for really strong, versatile route setting. How do you cultivate that?

That’s hard to say. I think it comes down to having a lot of different things blended together. Fun movement, really fine-tuned foot placements, and flow. I think we find a lot of that because we spend a long, long time forerunning. A lot of gyms don’t do that.

We try to shoot for a 60-40 approach, where we’re spending 60% of the time setting and 40% forerunning. So we try our best to take a very slow approach when we’re climbing our climbs, with every single grade from V0 up to V10+. Even if we feel, ‘Yeah, it was good, but it could be just a little better,’ we keep working on it.

We also try to be generous when it comes to making sure most climbs are for everyone. Not every climb is going to be for everyone. You have to understand that, at a certain point, a move isn’t going to work if it’s for everyone. But we try our best to have an option for every climber on every problem.

Like different ape indexes, heights, weights…?

Yeah, exactly. Ape indexes. Heights. Ages. Anything that could separate someone from being able to do a move, maybe they have another way around it. People love to have the creative outlet of figuring out their own beta.

Sometimes I think setters get too worried about forcing beta, but if someone does it differently, they probably had so much fun finding another way to do it. And that’s great. That’s the whole point. I just want the climber to have fun. Sure, I want them to do the moves and learn new moves, but my primary goal is that people are having fun.

You talked about a 60-40 ratio between setting and forerunning. Can you explain what “forerunning” is for those who may not know?

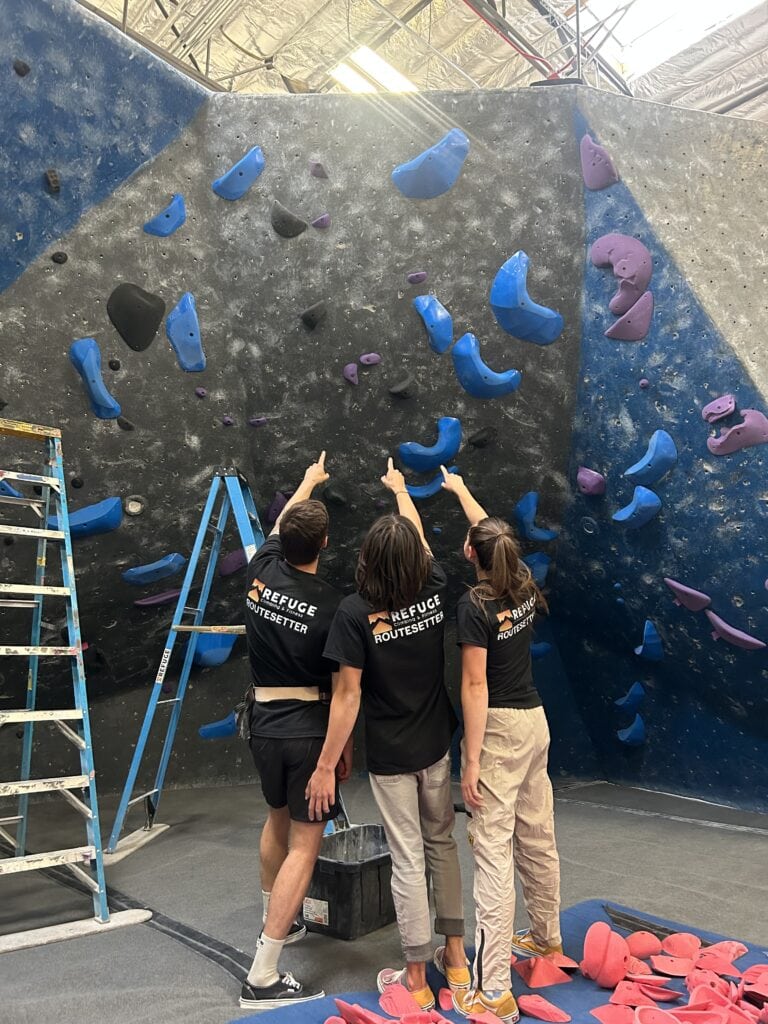

Yeah, forerunning is trying the boulders as a team. So we set, break for lunch, chill for a minute, and then everyone climbs all the climbs that we’ve set. We warm up first, and then go through every climb, working them as thoroughly as possible. Everyone does the first boulder. Everyone does the second boulder…. You get the idea.

And everyone has free rein to say whatever they want about anyone else’s climbs. No one is better than anyone else, no matter how long they’ve been setting. The more opinions we get, the better.

So everyone tries the climbs. We share what we think about them. We tweak. We try again. Tweak. Try again. Once we’re satisfied, we all move on to the next boulder. We do that with every single climb until we’ve done all of them. Every single climb that goes up in the gym goes through the same routine, even all the way down to our easiest grades (VB and V0).

How many setters do you have? How many people are doing all these problems?

Our primary team is five or six people. So there are at least five or six climbers testing every problem that goes up. We also have dedicated forerunners that come in regularly. These are people that are just coming to climb with us for the forerunning process, good “sample” climbers, basically. Like, maybe we want someone that’s right in the middle ground, or strong enough to help us with the hardest climbs.

Can you set a problem that’s too hard for you, personally, to climb? How does that work?

Yeah, but it’s hard. That’s one of the hardest things about setting—trying to set moves that you know you can’t do—because once a move leaves your realm of possibility, you don’t know whether it’s just a little harder or way harder. It’s impossible to know.

That’s where really extensive setting experience comes into play. Maybe you can’t do the problem, but you know the angle of the wall. The texture of the grip. The body position. So you have an idea of how hard it’s going to be. You can’t do it, but you know it’s possible. It’s maybe just outside of your reach, or just outside of this person’s reach who you know is a little stronger than you, so you have an idea.

It’s very difficult though. Trying to figure that out takes a lot of thinking and spatial awareness. Thinking about the moves in your head, feeling the grips, knowing how it’s going to go. It’s tough, but we all do it. There’s no setter who sets all the hard problems because he’s the strongest. Everyone sets every grade.

But during the forerunning process, does at least one of you have to be able to fully send a problem for it to go up?

Not send it, but we all work as hard as we can to make sure we can do every single move of every single climb. So if we set a nails-hard black tag (V10+), our hardest grade, we are going to try our best to make sure each of the moves go.

We don’t like to have climbs that are like question marks. Why put a climb up, if we’re not even sure if it goes? I don’t like that. It’s like you’re a chef and you’re giving someone something you’ve never tasted. You’re serving a meal that you don’t even know is good. There’s very rarely a climb that we put up that doesn’t either a) get sent or b) all the moves get done individually.

Sometimes that’s really fun, because one person’s good at one move and another is good at another. So I’ll do the big power move, and then another setter, Lily, will do the techie, little crimp move, and we’ll do it as a team.

Can you tell us about your favorite problem you’ve set?

I don’t know if I could pick a favorite. A lot of the people that taught me to set kind of instilled it in me that you shouldn’t have too much attachment to your problems. Setting is a very ephemeral process. Once the climb is up, it’s going to be there for seven and a half weeks, and then it’s gone forever. You might like it and climb it a lot, but at the end of the day it’s going to be gone… and you’re going to set a new one.

Have you ever written down or recorded a sequence that you really liked because you didn’t want to forget it?

Well, we are really fortunate because here at our gym, we have a YouTuber, Miguel, who has a very large following and he does weekly videos. It’s really fun because I can look back and I can have a catalog of all the climbs. But I also just have a very weird memory with moves and climbs.

Weird in a good way?

Yeah, like weird in a good way [laughs]! I can remember a lot of what I’ve set, and I know it’s the same for some of the other setters. I’ll talk to Lily and I’ll be like, “Do you remember that one climb that was here with this move and that move?” And she’ll immediately know what I’m talking about.

We’re crazy when it comes to remembering climbs, because I can barely remember what I had for breakfast. But this is something we love. When you set a climb you really like, you’re making a little block in your brain where you’re like, “Oh, now I have another sequence,” and you can break out that sequence again in the future.

You just keep all these pieces and you pull them out when you build new climbs. You pull from the Internet. You pull from your Instagram feed. Pull from the rock outside. Pull from some building that had a weird feature on it and looked cool. Then once you’re sitting there in front of the wall and you have to set a climb, you start blending that stuff and throwing it up on the wall.

But to answer your question, no, I couldn’t think of a single climb. I remember a lot of fun climbs, but it’s hard to name one that stands out.

In your experience, can you make a living as a full-time route setter?

I think it’s very region specific. If you don’t live in a place that has many gyms and is open to freelance setting, then no way. You can’t make a living as a setter, in my opinion. You need some sort of secondary income. Most setters also do something else at the gym, or have a different job. So you’ll set a few days and then you’ll go do your other job. It’s very gig-y and that’s fine.

But it’s a bit unfortunate because setting is a hard skill to craft. It’s specialized. People underestimate the time it takes to be a good setter. Maybe you can set a few good problems, but it takes a long time to get consistent and be able to put up good skeletons and boulders all the time, and do it week after week after week.

It’s also a very physical job. It’s tiring. There’s a lot of work that goes into it. Unfortunately, with the current ecosystem, it’s not a high-paying job. It’s a very low-paying job for most people. Most people can’t make it work as a living. They can only do it as a hobby, or something that they love to do but can’t really invest in.

I have other jobs. I do other jobs here [at The Refuge] and I have other jobs outside of the gym. I have to be doing something outside of this. I wouldn’t be able to survive with just route setting. It’s tough. I think the business can still grow. But I think that setting has a long way to go before it’s feasible as a real “profession.”

A lot of people find that climbing gyms tend to grade softer than outdoor boulders. Is that ever a conscious decision, maybe to entice newer climbers to keep coming back? Or is it just the nature of indoor climbing?

It’s hard to really nail outdoor, because the rock is always going to be the rock. It’s almost impossible to get your grades quite like that. But hey, there are wide swings outside too. There are V5s that are impossible for most, and V5s that V4 climbers can flash. There are always wide swings, and the same thing is true in the gym. Style is everything. If you’re climbing a climb that’s your style, it’s going to feel easy. If you’re climbing a climb that’s not, it’s going to feel hard.

But yeah, so we try to do it justice. Like, we try to be a little bit closer to outdoor grades. We’re not there, and I don’t think there are a lot of gyms that are there… except for Japanese gyms, maybe. But yeah, a lot of gyms do lean too hard into giving you the next grade very easily. They soften it up so your progression is easier. We try to make it a challenge. We want you to get stronger. We want you to have fun. But we want you to work for it.

As far as motivating new climbers, I think every gym does that to a degree. It’s more about how hard you’re leaning into it. Some gyms are really giving it to you. We don’t want to do that, we just try to have something for everyone. Maybe there’s an easier one of this grade and a harder one of this grade. We want it to be fair.

That’s because, in my experience, people almost don’t take a victory when they know it’s too easy. Like, if you give them a really soft V5 or whatever, and a lot of people that project that grade do it really quickly, then they don’t actually feel that proud of themself. So you can grade soft, but at the end of the day, you’re almost doing your members a disservice.

Are you certified as a USA Climbing setter? Can you speak to those certs and what’s entailed to set at that level?

I don’t have any experience with USA Climbing when it comes to route setting, I’m a coach, so we put all our kids through USA Climbing and we see the boulders and stuff. But their route setting certification, I’ve never taken part in. It’s very hard to get into. It’s very expensive, and I honestly think it’s a bit of a gatekeep for a lot of people that aren’t willing to travel and spend that much money for a certification.

I am interested in getting a certification, though, just for the sake of having something tangible on my resume. Like, I’ve been doing this job, but you really don’t have anything to say if you went to another job that you. It’s hard to come in and just say, “Hey, I’m a good setter, I promise.” If you have Level 2 or Level 3, that’s something that you can carry with you, that speaks for itself.

So you’d say the biggest obstacle for USAC route setting isn’t skill, it’s money?

Well yeah, and having the time to travel and take the clinics, and registering quickly to get in. Maybe knowing someone at USA Climbing can help you. I don’t know. It’s hard. It’s expensive. You have to pay for certification. You have to pay for the annual subscription…

[For reference, participation fees for a USAC Level 1 setting clinic are $500, and all participants must also have an active USAC Routesetter membership ($100/year). For Level 2, prices increase to $800, and clinics are only held four times per year at select host facilities—each of which must be Championship level competition hosts. For a full matrix of USA Climbing’s Routesetter Certifications, see HERE]

But you have set for USA Climbing competitions before, so let’s talk comp setting. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Yeah, we’ve totally set comps here for USAC. We have that coming up again in October this year. So, that and regular citizen’s comps are totally different things. When you’re setting for the USA Climbing comps, you have to take height into consideration so much more. Height and gender are very important.

If you’re setting for Youth D, for example, that’s a child. Your climbs have to be for a child. It’s not the problems we set normally, ones that are designed to be for everyone, where short people and tall people should be able to have a way to do them. With USAC setting, you’re making a problem to challenge a very specific height range. You have to totally rethink the way you’re spatially looking at your reaches.

Setting for general citizen’s comps is easier. You’re just trying to get more innovative movement out there. It’s about getting creative, a little bit more feature-heavy. Adding bigger, more open movement with large featured holds that you really have to manipulate. Comp problems have a bit more jumpiness, throwiness, delicate slab work…

A lot of people don’t like comp movement, but I think it’s great. People hate on it because it’s another skill. You have to learn totally new moves. Paddle dynos, jump catches, toe hook snags, all these movements that are totally new and unique to comp style. You probably don’t like it because it’s like a whole new thing to learn. It takes some time, but then you get it, and you can do it the next time you see it, and it feels cool. It’s an amazing feeling. People should be a bit more open to it.

Last question. As briefly as possible, what is “good” route setting to you?

Man.. that’s so hard. Route setting isn’t about one boulder. It’s not about your climbs. Good route setting is a team effort. Once you’ve put your last hold on the wall and you’ve finished your climb—before forerunning—your climb is no longer yours. Now it’s the whole team’s.

So accepting input and then changing your boulders to become challenging, enjoyable movement that’s relatively doable for most body types… That’s where good setting really comes in. A good boulder can be a good boulder, but a really good gym is diverse, with a vast range of movement and difficulty.

So you’d say that making a singular, good problem is not what setting is about. Instead, it’s about having a diverse ecosystem of problems?

Exactly. That’s what I’m getting at. It’s less about one boulder. It’s less about the individual. It’s about the team and having a full body of work and how every climb fits with every other climb.

Think of it like this, you can have one good song on an album, but it’s not going to be Album of the Year and no one’s going to care. You want a full body of work. Something you can listen to all the way through and enjoy all aspects of. Like when you listen to an album and you’re thinking, “This one was really gritty, but this one was really soft and melodic,” and they mesh together in a nice way, instead of it being one sound all the way through.

Good route setting is finding that balance, making everything come together. When you have a really beautiful ecosystem across the whole gym… That’s what we want.